Dear friends, we hope this letter finds you well. Since our last letter we have experienced heightened volatility (not the good kind, sorry to report). The month of October has a reputation for being “scary”. To date, this October has been no exception.

OCTOBER: This is one of the peculiarly dangerous months to speculate in stocks. The others are July, January, September, April, November, May, March, June, December, August, and February.

~ Mark Twain

Headlines and news reports regarding market declines can cause unease, but take some comfort in knowing that it is perfectly normal for the stock market to experience schisms. We understand that there have been ~ 218 declines in the S&P 500 of 5% or more since 1920. Much of this volatility is rooted in investor psychology (i.e. emotion / sentiment; fear / greed).

In our last correspondence, we talked about market cycles. The psychological factors that contribute to market cycles is the topic for this quarter’s letter. As we will see, investor psychology is at the root of much of stock market volatility. Those that understand investor psychology and its role in market cycles are better equipped to weather, or possibly exploit, volatility. It is our hope that this discussion will make you better informed and to give you some perspective on recent market volatility. Fortuitously, Howard Marks, a truly great investor and one of our role models, recently released a book on this very topic. This letter borrows heavily from Marks – we will cite him throughout our discussion.

The Speculative Return

It is important to understand that the return that you earn from owning stocks is ultimately a function of the performance of the business in which you have invested. All investments, be it common stocks, bonds, real estate, etc. derive their value, and hence their worth, from what they produce (i.e. what you can get out of them in terms of earnings). This is a simplistic statement but, at times, it is lost on some investors. If you invested in “rare” Beanie Babies in the 1990’s you may be acutely aware of this iron law.

It is not surprising then that the return on a basket of stocks such as, say, the S&P 500, converges around a central figure (9-10%), on average, over long time periods. Why? Because that is what has been produced (historically) in terms of earnings and dividends, from a diversified basket of large U.S. companies, on average, over long time periods.

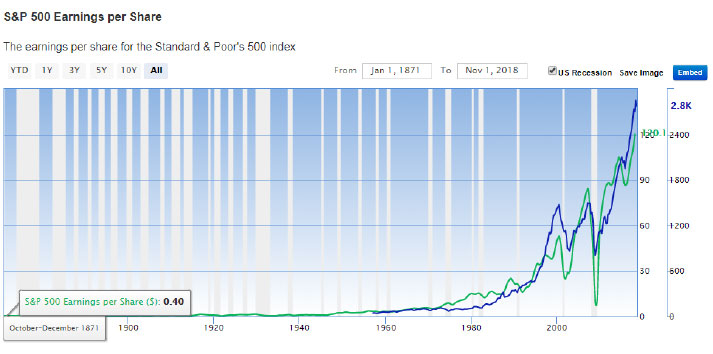

As earnings go up, the value or worth of stocks (like say, the S&P 500) ultimately should follow (but this relationship is never linear and can diverge for long periods). Observe the following chart of the S&P 500 Index (blue line) plotted against the earnings (collectively) of the companies that make up the index.

In the short run, all bets are off however. Truly, the market return in a given year (or 2-3 years for that matter) could be just about anything. This is so, in part, because of investor psychology / sentiment / mercurial attitudes about risk (greed / fear). The following chart1 illustrates this concept – price oscillates around “intrinsic value” (a subjective figure, hence the bounded lines).

The fortunes of companies, industries and the economy do not fully explain the swings in the stock market – a lot is owing to investor psychology. The economy and companies, in aggregate, change very modestly in the short run, but stock prices can fluctuate much more. Much of this fluctuation is explained by the psychology of investors. Here is Marks on this topichttps://www.barrons.com/articles/an-investment-pros-advice-on-surviving-the-market-storm-1540490857?mod=hp_DAY_42:

“….the ups and downs of economies are usually blamed for fluctuations in corporate profits, and fluctuations in profits for the rise and fall of securities markets. However, in recessions and recoveries, economic growth usually deviates from its trend line rate by only a few percentage points”.

It is important to know that, in the very long run, the swings owing to sentiment pretty much cancel out leaving the investor with a return that is explained, roughly, by the performance of the underlying business, farm, apartment building, etc.

This notion can be seen in John Bogle’s formula for estimating the return on U.S. stocks over the coming decade.

Bogle’s formula is this:

Future Market Returns = Dividend Yield + Earnings Growth +/- Change in P/E Ratio

It is the last component of return that is relevant to our discussion. The change in P/E ratio (price / earnings), referred to by Bogle as the “speculative return”, tells us how much investors are willing to pay for a dollar of earnings. It can be interpreted as a gauge of sentiment / optimism. This component gravitates to zero over long time periods leaving you with what is, essentially, the return generated by the underlying businesses. As Bogle explains, “So these ups and downs are basically,…because one always likes to quote Shakespeare, like ‘a tale told by an idiot: full of sound and fury, signifying nothing’”3.

So how much can a change in sentiment affect returns? A lot. For some context, here are some notable examples4 (Source: John Bogle, “Don’t Count on It”). Take a look at the third column, which shows the effect on 10-year returns:

So, despite that the speculative component of return cancels out over time, it can be very consequential over shorter time periods (decades, in our chart above). Put simply, if you buy the market when it is dear your return over the subsequent period can potentially be significantly lower if / when sentiment reverts to the mean. Paying high prices is an anchor on long term returns.

Here is Howard Marks talking about this very idea in his recent book5:

“…it seems rational that, in the long run, stocks overall should provide returns in line with the sum of their dividends plus the trend line growth in corporate profits, or something in the mid-to-high single digits. When they return much more than that for a while, that return is likely to prove to have been excessive—borrowing from the future and thus rendering stocks risky—meaning a downward correction is now in order”.

The Role of Investor Psychology in Market Cycles

Stock market cycles are characterized by changes in sentiment / psychology. Generally, when things are good and stock prices have been rising investors have a rosy outlook on the future. They are more concerned with “missing out” than losing money. They experience feelings of envy and greed. They have difficulty in conceiving of events that could derail the market. They buy on any dips, confident that the market will continue to go up. Marks:

“When events are predominantly positive and psychology is rosy, negative developments tend to be overlooked, everything is interpreted favorably, and things are often thought to be incapable of taking a turn for the worse. The logic supporting an expectation of further advances appears irresistible; past constraints and norms are ignored or rationalized away; and anyone imagining limitations on the positive future is dismissed as an old fogey lacking imagination. The potential for gains comes to be viewed as infinite. Asset prices rise, encouraging further optimism…and when events are down, so are investors. They think of the markets as a place to lose money, risk as something to be avoided at all cost, and losses as depressingly likely6”.

Here is Howard Marks explaining the psychological elements of bull markets:

- The economy is growing and the economic reports are positive.

- Corporate earnings are rising and beating expectations.

- The media carry only good news.

- Securities markets are rising.

- Investors grow increasingly confident and optimistic.

- Risk is perceived as being scarce and benign. Investors think of risk-bearing as a sure route to profit.

- Greed motivates behavior. Asset prices rise beyond intrinsic value.

- Skepticism is low and faith is high.

- No one can imagine things going wrong.

- Those who’ve remained on the sidelines feel remorse; thus they capitulate and buy.

So what does Marks prescribe for investors in a market characterized by these elements? “Prospective returns are low (or negative). Risk is high. Investors should forget about missing opportunity and worry only about losing money. This is the time for caution!7”

He goes to explain what happens in a market downswing:

- The economy is slowing; reports are negative.

- Corporate earnings are flat or declining, and falling short of projections.

- Media report only bad news.

- Securities markets drop.

- Investors become worried and depressed.

- Risk is seen as being everywhere. Investors see risk-bearing as nothing but a way to lose money.

- Fear dominates investor psychology.

- Asset prices fall below intrinsic value.

- Skepticism is high and faith is low.

- No one considers improvement possible.

- No outcome seems too negative to happen.

- Everyone assumes things will get worse forever.

- Investors ignore the possibility of missing opportunity and worry only about losing money.

- Prices reach new lows. The media fixate on this depressing trend.

- Investors become depressed and panicked.

- Security holders feel dumb and disillusioned.

Marks advice: “Implied prospective returns are sky-high. Risk is low. Investors should forget about the risk of losing money and worry only about missing opportunity. This is the time to be aggressive!8”

So, the point is that psychology contributes to, and amplifies, stock market volatility. The astute investor can take cues from the behaviour of the herd.

A Bipolar Orientation

Marks observes, and our experience confirms, that investors’ psyche is often at extremes – it has a bipolar orientation. It seems that investors, en masse, are either felling really good or they are despondent. What causes the swing between these emotions?

“In individuals, insanity is rare; but in groups, parties, nations and epochs, it is the rule”

~ Philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche

Often, a trigger event (rarely conceivable in advance) leads to a tipping point in investor sentiment. Sometimes it is not clear why this change in sentiment occurs. Often, when valuations are high and sentiment is decidedly bullish for an extended period a trigger event (or a collusion of several such events), often unforeseen by just about everyone, works to create some measure of doubt or worry / fear. Due to a feedback mechanism inherent in crowds, a vicious circle is created (selling begets selling, which begets more selling). This mechanism works in both directions and serves to amplify volatility – setting off a cascade effect.

Here is Marks explaining:

“It all seems so obvious: investors rarely maintain objective, rational, neutral and stable positions. First they exhibit high levels of optimism, greed, risk tolerance and credulousness, and their resulting behavior causes asset prices to rise, potential returns to fall, and risk to increase. But then, for some reason – perhaps the arrival of a tipping point—they switch to pessimism, fear, risk aversion and skepticism, and this causes asset prices to fall, prospective returns to rise, and risk to decrease. Notably, each group of phenomena tends to happen in unison, and the swing from one to the other often goes far beyond what reason might call for. That’s one of the crazy things: in the real world, things generally fluctuate between “pretty good” and “not so hot.” But in the world of investing, perception often swings from “flawless” to “hopeless.” The pendulum careens from one extreme to the other…9.”

A Matter of Perspective

Depending on the mood of the market, investors have a tendency to interpret news / events with “selective perception and skewed interpretation10”. Marks:

“…sometimes they take note of only positive events and ignore the negative ones, and sometimes the opposite is true. And sometimes they view events in a positive light, and sometimes it’s negative. But rarely are their perceptions and interpretations balanced”.

Marks provides the following examples of how investors interpret data / events with a positive bias. Notice the bias in interpretation.

Strong data: economy strengthening—stocks rally

Weak data: Fed likely to ease—stocks rally

Banks make $4 billion: business conditions favorable—stocks rally

Banks lose $4 billion: bad news out of the way—stocks rally

Oil spikes: growing global economy contributing to demand—stocks rally

Oil drops: more purchasing power for the consumer—stocks rally

Dollar plunges: great for exporters—stocks rally

Dollar strengthens: great for companies that buy from abroad—stocks rally

Inflation spikes: will cause assets to appreciate—stocks rally

Inflation drops: improves quality of earnings—stocks rally.

Of course, the same behavior also applies in the opposite direction. When psychology is negative and markets have been falling for a while, everything is capable of being interpreted negatively”.

So, the point is that the mood of the market affects investors’ interpretation of data / events. This skewed interpretation contributes to swings in sentiment between cheerful and depressive. As Marks explains, “[the market] just picks funny things to obsess about….you can’t attach too much intelligence to the market’s daily fluctuations11”.

Tying it all Together

We hope that this primer on investor psychology gives you some perspective on the recent stock market volatility. To some extent, market participants have recently decided to focus on the negatives, fear of losing money has displaced fear of missing out and skepticism has replaced optimism.

Of course, the question that is important for you, and for us, is “How can we use knowledge of investor psychology to our advantage?” Our answer, and Marks agrees, is that it extremely important to know where you stand in the market cycle and adjust your behaviour accordingly (i.e. prepare / adjust). Marks’ prescription is as follows:

- Take the temperature of the market (i.e. assess the prevailing mood). Incorporate this qualitative input into your positioning (i.e. level of aggressiveness / conservatism);

▪ How optimistic / skeptical are investors? How rich are securities prices? How are investors interpreting news – with rose coloured glasses or doom and gloom? Are investors experiencing “FOMO” (fear of missing out)? Are investors “all in” on stocks? - Resist psychological excesses;

▪ Investors benefit from being unemotional. - Be somewhat contrarian at market extremes;

▪ Generally, investors tend to behave in a herd-like fashion. Marks’ advice, which we endorse and practice, is to act somewhat contrarian. Marks: “it seems to be hard-wired into most people’s psyches to become more optimistic and risk-tolerant when things are going well, and then more worried and risk-averse when things turn downward. That means they’re most willing to buy when they should be most cautious, and most reluctant to buy when they should be most aggressive. Superior investors recognize this and strive to behave as contrarians12”.

So, what does Marks think about the stock market today? Here is his response in a recent (October 25, 2018) Barron’s article13:

“To me, the main question is: Is it time for offense or defense? And I still think it is time for defense, predominantly. It’s not 100%, but at this point I would worry more about losing money than I would about missing opportunities and it is time for caution”.

We agree. Best wishes to you and your family from your Apex team Advisors and staff: Shawn, Scott, Mike, John, Will, Denise, Paul, Tina, Denise, Lisa, Marta, Darlene and Sharon.

Disclaimer:

The information contained herein was obtained from sources believed to be reliable, however, we cannot represent that it is accurate or complete. This report is provided as a general source of information and should not be considered personal investment advice or solicitation to buy or sell any securities mentioned. The views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of ACPI.

Aligned Capital Partners Inc. is a member of the Canadian Investor Protection Fund and the Investment Industry Regulatory Organization of Canada.

1 Marks, Howard. Mastering the Market Cycle: Getting the Odds on Your Side, October 2018.

2 ibid.

3 “Bogle: Market Turbulence Just a Lot of ‘Sound and Fury’”, Morningstar, John Bogle, https://www.morningstar.com/videos/670432/bogle-market-turbulence-just-a-lot-of-sound-and-fu.html

4 The John Bogle Expected Return Formula”, A Wealth of Common Sense, Ben Carlson, Sept. 13, 2016, https://awealthofcommonsense.com/2016/09/the-john-bogle-expected-return-formula/

5 Marks, Howard. Mastering the Market Cycle: Getting the Odds on Your Side, October 2018.

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 Mastering the Market Cycle: Getting the Odds on Your Side, Howard Marks, 2018.

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid.

13 “An Investment Pro’s Advice on Surviving the Market Storm”, Barron’s, Lawrence C. Strauss, October 25, 2018, https://www.barrons.com/articles/an-investment-pros-advice-on-surviving-the-market-storm-1540490857?mod=hp_DAY_4