We hope that this letter finds you healthy and in good spirits. The year 2020 is one that we will all remember (and not fondly). Our hope is that you and your family members are managing well through this remarkable period of crisis.

We are encouraged to see progress on slowing of the pandemic that has plagued the World for several months. What is surprising, to many, about the pandemic-induced recession is the huge rally in U.S. stocks since the March lows. Amid a recession and great uncertainty, the U.S. stock market, as measured by the S&P 500, is just about back to its all-time high of 3,386 reached on February 19. What to make of this somewhat counterintuitive move in stock prices?

Ben Inker summed things up nicely in the title of a June 4 note to Grantham Mayo investors: “Uncertainty Has Rarely Been Higher; Oddly, Neither Has the Stock Market[1]”.

In this article, Inker summarized the situation as follows, “The current P/E on the U.S. market is in the top 10% of its history. The U.S. economy in contrast is in its worst 10%, perhaps even the worst 1%. In addition, everything is uncertain, perhaps to a unique degree”.

First, we can’t help but point out that recent stock moves are a good example of the futility in trying to predict what the market might do in the short run. The highly regarded fund manager Chuck Akre made this very observation in a recent note to investors:

The year 2020 should (but will not) dispel any faith remaining in market forecasts. Who predicted the coronavirus? Or, having successfully predicted the arrival of the coronavirus in early 2020, what would have been your forecast for the stock market this year? Let us re-frame the question: if you knew in advance that the unemployment rate in the United States would go from 3.5% in February to 11.1% in June (with a stop at 14.7% in April) what would be your prediction for the stock market? Down 30%? Down 40%? Down 50% or more? Instead, through June 30, the S&P 500 Total Return is down just over 3%[2].

Note: at time of writing, the total return (price appreciation plus dividends) on the S&P 500 year-to-date is ~ up 5%[3].

We are in a recession and weak economic indicators abound, but we cannot say that the rally in stocks is irrational. It could be that the market is looking “across the valley” and anticipating a strong recovery. The market might reflect on the pandemic as an exogeneous event that will abate, restoring confidence and economic activity. It could also be a function of the ultra-low interest rate environment, which may work to elevate the prices of financial assets like stocks.

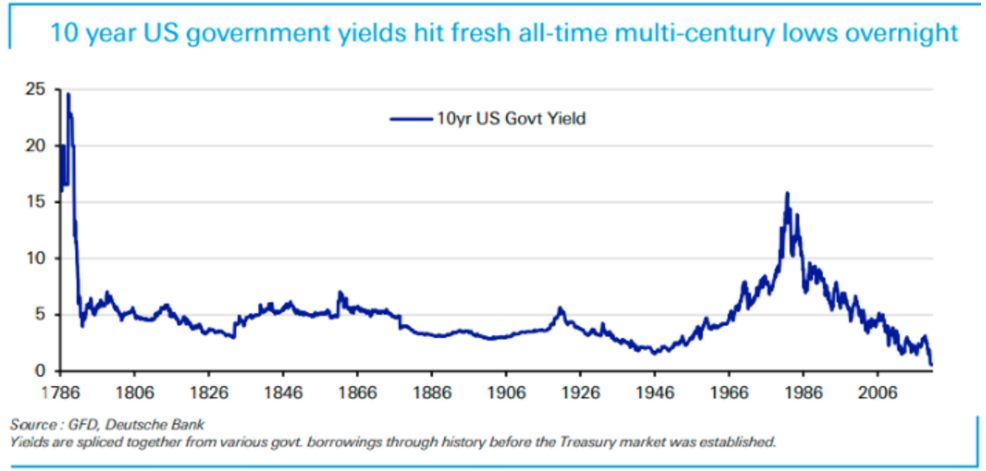

How low are interest rates? According to Deutsche Bank, the 10-year U.S. Treasury note yield fell as low as 0.520% in late July, marking a record that stretches back over 200 years (see chart below)[4].

We can only theorize about the mind of the market, but the latter explanation seems, to us, as one of the more credible.

Howard Marks provided some insight on what is driving markets higher in an August 5 memo to Oaktree investors. Marks’ view is that U.S. Government stimulus (including the purchase of Treasuries and other fixed income securities) and ultra-low interest rates might explain (in part) the move in U.S. stocks. Here, Marks explains:

“Lower interest rates increase the discounted present value of future cash flows and reduce the [expected] return demanded from every investment. In layman’s terms, when the fed funds rate is zero, 6% bonds look like a giveaway, so buyers bid them up until they yield less…..And Fed buying drives up the price of financial assets and puts money into sellers’ hands with which they can buy other assets, further elevating prices[5]”.

Government stimulus was necessary, to be sure, but it leads to the obvious question of what are the second-order effects of a decade of massive Government intervention (i.e. borrowing and asset purchases)? Are there negative implications that will manifest in the future? Here are Marks’ thoughts:

But what does it mean if the prices of stocks and listed credit instruments are where they are not primarily for fundamental reasons – such as current earnings and the outlook for future gains – but rather in large part because of the Fed’s buying, its injection of liquidity, and the resultant low cost of capital and low demanded returns? If high asset prices are substantially the result of tailwinds from technical factors such as these, does it mean those actions have to be continued in order for asset prices to remain high, and that if the Fed reduces its activity, those prices will fall? And that leads to the ultimate question: can the Fed keep it up forever? Are there any limits on its ability to create bank reserves, buy assets and expand its balance sheet? And are there limits on the Treasury’s willingness to run deficits, now that it has taken this year’s to $4 trillion and shown an inclination to go well beyond that?[6]

Another new and somewhat surprising development in the stock market is signs of speculative activity, the like of which we haven’t seen since perhaps the late 1990’s. I wouldn’t put too much stock into this type of anecdotal observation; it’s not a signal, but it does speak to the mood of the market and we should take note. Risk-taking is in vogue; greed has eclipsed fear (for now). “Day trading” has once again become fashionable. This type of investor behaviour suggests that caution is in order. As Buffett counsels, “The less prudence with which others conduct their affairs, the greater the prudence with which we should conduct our own affairs[7].”

Author and portfolio manager Ben Carlson took stock of this situation in a July 27 article[8]:

Tech stocks are going crazy? Check

IPOs are on fire? Check

Retail day-trading is going bananas? Check

People are proclaiming we’ve entered a “new” economy? Check

Warren Buffett is getting mocked relentlessly? Check

Investors are throwing money at unproven business models with no profits? Check

Value stocks are getting crushed by growth stocks? Check

Small cap stocks are getting left in the dust by large cap stocks? Check

Carlson concludes that “This is a description of what went during the insanity of the late-1990s dot-com bubble…and what’s happening in 2020”.

We wouldn’t go as far to characterize the stock market today as a bubble. Prices, generally, look high using simple metrics like P/E ratios, etc., but they are not offensive, particularly when you factor in a low discount rate (i.e. interest rates are considered to be a key input to stock valuation). We must entertain that stock valuations could remain elevated for many years. Perhaps, a generation.

The problem with waiting for the “normal” to return, is that you can’t be certain whether the world has undergone a paradigm shift (i.e. there is a “new normal”). Occasionally, it is different this time. There are risks to being invested in stocks that must be weighed against the risk of not being so invested.

Stocks offer the prospect of maintaining or growing the purchasing power of your savings over the long term, whereas fixed income securities, based on today’s yields, are unlikely to do so. Ben Inker eloquently summed up the situation as follows, “Moving from stocks to cash would be trading the possibility of a horrible outcome against the certainty of an inadequate one[9].

This era of higher stock valuations creates a quandary for today’s investor. Prior to the Financial Crisis, investors could count on bonds and GIC’s as a ballast to their stock holdings. The traditional “60/40” portfolio (i.e. 60% stocks, 40% fixed income) served them well. When stock prices fell, these moves were buffered by the allocation to fixed income (which often increased in price). Bonds buffered volatility and contributed to portfolio returns. But with paltry yields on bonds / GIC’s etc., the case for fixed income is less convincing; fixed income still offers a safe harbour but with the expectation of returns that will potentially be negative in a real sense (i.e. after inflation).

The solution for many investors has been to simply allocate more money to stocks. Yesterday’s 60/40 investor is today’s 70/30 investor. This is perfectly understandable, if one has the requisite level of risk tolerance, capacity for loss, and time horizon to accommodate this shift. We must guard against risk tolerance creep / drift.

Many investors have rationally allocated more money to stocks because they are widely seen as the best relative bet. We can’t argue with this logic – many stocks offer the prospect of dividend yields that exceed the rate of interest on long-term bonds and, additionally, the potential for growth. We like stocks for the long run, today and everyday. The race is not always to the swift, nor the battle to the strong, but that’s the way to bet! (we borrowed that from Bill Miller, quoting Justice Holmes[10])

However, as we have argued in past correspondence, cash (or short-term fixed income securities) has value that lies in its optionality; having cash on hand to potentially capitalize on the future opportunity set may be, to an extent, a wise idea. Market disruptions and fear can create opportunity, but only if you have cash.

As we have explained in past correspondence, one of the most important decisions in investing is that of “cycle positioning” (i.e. where you position yourself on the continuum of aggressiveness vs. defensiveness). This is a very useful mental construct that we borrowed from Howard Marks. Cycle positioning requires judgement about risk and prospective return. It figures prominently in our thinking. At present, we have a bias toward defensiveness because high stock valuations point to lower prospective returns and a lower margin of safety.

A common idea is this era of low interest rates is to allocate money to “alternative” assets such as gold. The “gold bugs” (those who believe that gold is a safer investment than paper money) reasoning, often, is that the U.S. dollar and currencies, generally, are unsound, as they are not backed by anything tangible. They reason that we cannot count on paper currency as a store of value. The U.S. dollar has, in fact, recently lost ground relative to many other currencies, which can be seen in the chart below of The U.S. Dollar Index (DXY) a measure of the value of the United States dollar relative to a basket of foreign currencies[11].

In July, Goldman Sachs strategists commented that, “Real concerns around the longevity of the U.S. dollar as a reserve currency have started to emerge. Gold is the currency of last resort, particularly in an environment like the current one where governments are debasing their fiat currencies [i.e. paper currency not backed by gold; the value is established by Governments] and pushing real interest rates to all-time lows[12]”.

In Goldman’s view, “the growing level of debt in the U.S. — which now exceeds 80 per cent of the nation’s gross domestic product — and elsewhere, boosts the risk that central banks and governments may allow inflation to accelerate[13]”.

This is a plausible theory. Inflation is a risk that has been on the back burner for many years. It is possible that we could see a resurgence given the lack of discipline on the part of Governments to reign in deficits and borrowings. We don’t think that anyone can predict whether or when this might happen, but it is a credible worry. In an August 12, 2020 note to investors James Montier of Grantham Mayo commented, quoting Howard Marks, that the future path of things such as inflation are “unknowable”:

“Howard Marks of Oaktree Capital often talks about there being two kinds of investors. The two groups can be broadly distinguished by their attitudes toward the future. The first camp is best described as “I know” investors. They think that knowledge of the future course of events such as growth and interest rates is vital to investing. They are confident that such knowledge is attainable, and they “know” they can forecast accurately. They are very comfortable investing on the basis of their views. They freely admit that others will be trying to do the same thing, but their insight is better: it is their edge. Such investors are very popular at dinner parties because they will chatter on about pretty much any subject.

In contrast, the second group of investors studied at the “I don’t know” school. They hold some very different beliefs about the way you should approach investing. They believe you can’t know the future, and, in fact, you don’t need to know the future in order to invest. Driven by this explicit embrace of uncertainty, they insist on a margin of safety when investing: valuation is front and foremost in their approach. This group is not particularly popular at dinner parties (or maybe it’s just me) as the frequent refrain of “I don’t know” in response to questions is not amazingly stimulating on the conversation front[14]”.

We, too, are in the camp that acknowledges our collective ignorance about the future with respect to interest rates, inflation, markets, metals, currencies, etc.

We acknowledge that gold has had a big move recently (bullion is up ~ 23% this year according to the Financial Post[15]), as more and more investors are drawn to this idea. To some extent, a bandwagon effect may be at work. Here is Warren Buffett on the motivations of gold buyers:

“What motivates most gold purchasers is their belief that the ranks of the fearful will grow. During the past decade that belief has proved correct. Beyond that, the rising price has on its own generated additional buying enthusiasm, attracting purchasers who see the rise as validating an investment thesis. As ‘bandwagon’ investors join any party, they create their own truth – for a while[16].”

We note, however, the huge opportunity cost of investing in gold, historically, relative to U.S. stocks over the long haul. In his 2018 Chairman’s Letter to Berkshire shareholders, Warren Buffett commented that U.S. stocks have trounced an investment in gold, historically, despite large U.S. deficits and borrowing. In his words, “The magical metal was no match for the American mettle[17]”. In this letter, Buffett compared an investment in gold in 1942 (the year that he bought his first shares of stock) and an equal dollar amount in the S&P 500. Here, are his calculations and conclusion:

“Those who regularly preach doom because of government budget deficits (as I regularly did myself for many years) might note that our country’s national debt has increased roughly 400-fold during the last of my 77-year periods. That’s 40,000%! Suppose you had foreseen this increase and panicked at the prospect of runaway deficits and a worthless currency. To “protect” yourself, you might have eschewed stocks and opted instead to buy 31⁄4 ounces of gold with your $114.75. And what would that supposed protection have delivered? You would now have an asset worth about $4,200, less than 1% of what would have been realized from a simple unmanaged investment in American business”.

That gold has been a poor long-term investment shouldn’t come as a surprise – gold, unlike companies, doesn’t produce anything. Gold is something that is traded; you buy it with the hope that someone will take it off your hands at a higher price. This discussion reminds us a story related to us by Malcolm Gladwell about Ron Popeil, inventor and infomercial marketing genius behind numerous popular items such as the Chop-O-Matic, the Showtime Rotisserie Oven and Hair in a Can spray[18]. You will likely remember one of Popeil’s popular 1970’s “As Seen on TV” items, the Pocket Fisherman (Mike, undoubtedly had one of these. We can confirm that he is also the proud owner of a Big Mouth Billy Bass). The story goes as follows: a designer questioned the utility of the Pocket Fisherman to which Popeil’s father, S.J. Popeil, replied, “It’s not for using, it’s for gifting[19]”.

We prefer to keep things simple. As Einstein said there are five ascending levels of intelligence: smart, intelligent, brilliant, genius and simple. We do not attempt to forecast the intractable. We are not drawn to investments that have the potential to payoff sporadically and require deft timing.

On July 29, 2020, the CBC’s Don Pittis opined that, “When the U.S. economy starts chugging along again, gold will once again be expensive to hold and will still provide no investment return. The rule from the past is the only people who make money by buying gold are those who sell fairly quickly, before it plunges again[20]”.

We will conclude with a general thought. The “V” shaped recovery in stocks from the March-April sell-off may look to be counterintuitive but might be justified and rational. However, we continue to have a bias toward defensiveness. Cash, in some measure is prudent despite today’s unsatisfactory yield. And, importantly, be patient and think long-term – two qualities that are in short supply.

Best wishes to you and your family from your Apex team:

Shawn, Scott, Mike, John, Will, Denise E., Paul, Tina, Jason, Jeff, Greg, Denise N., Lisa, Marta, Darlene, Paula, Andrene and Sharon.

Disclaimer:

The information contained herein was obtained from sources believed to be reliable, however, we cannot represent that it is accurate or complete. This report is provided as a general source of information and should not be considered personal investment advice or solicitation to buy or sell any securities mentioned. The views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of ACPI.

Aligned Capital Partners Inc. is a member of the Canadian Investor Protection Fund and the Investment Industry Regulatory Organization of Canada.

[1] “Uncertainty Has Seldom Been Higher”, Ben Inker, GMO Q1 Quarterly Letter, https://www.gmo.com/americas/research-library/1q-2020-gmo-quarterly-letter/

[2] Akre Focus Fund Commentary Second Quarter 2020, https://www.akrefund.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Akre-Focus-Fund-Quarterly-Commentary-2020-Q2.pdf

[3] https://www.slickcharts.com/sp500/returns/ytd

[4] “10-year Treasury yield plunged to its lowest in 234 years, says Deutsche Bank”, Sunny Oh, MarketWatch, Aug. 1, 2020, https://www.marketwatch.com/story/10-year-treasury-yield-plunged-to-its-lowest-in-234-years-says-deutsche-bank-11596214464

[5] “Time for Thinking”, Howard Marks, Oaktree Capital Management, August 5, 2020, https://www.oaktreecapital.com/insights/howard-marks-memos

[6] “Time for Thinking”, Howard Marks, Oaktree Capital, August 5, 2020, https://www.oaktreecapital.com/insights/howard-marks-memos

[7] 2017 Berkshire Hathaway Chairman’s Letter, https://www.berkshirehathaway.com/letters/2017ltr.pdf

[8] “Patience is Virtue No One Has Time For Anymore”, Ben Carlson, A Wealth of Common Sense, July 27, 2020, https://awealthofcommonsense.com/2020/07/patience-is-virtue-no-one-has-time-for-anymore/

[9] “UNCERTAINTY HAS SELDOM BEEN HIGHER. Oddly, Neither Has the Stock Market”, Ben Inker, https://www.gmo.com/americas/research-library/1q-2020-gmo-quarterly-letter/

[10] Bill Miller 4Q 2019 Market Letter, January 13, 2020, https://millervalue.com/bill-miller-4q-2019-market-letter/

[11] https://www.marketwatch.com/investing/index/dxy

[12] “Goldman warns the U.S. dollar’s role as world reserve currency is at risk”, John Ainger, Bloomberg News, July 28, 2020, https://financialpost.com/investing/goldman-warns-the-u-s-dollars-role-as-world-reserve-currency-is-at-risk

[13] Ibid.

[14] “REASONS (NOT) TO BE CHEERFUL, Certainty, Absurdity, and Fallacious Narratives”, James Montier, GMO, August 12, 2020, https://www.gmo.com/americas/research-library/reasons-not-to-be-cheerful/

[15] “The stars have aligned for gold investors, but beware the tarnish, says BMO’s Brian Belski”, Pamela Heaven, Financial Post, August 17, 2020, https://financialpost.com/executive/executive-summary/posthaste-the-stars-have-aligned-for-gold-investors-but-beware-the-tarnish-says-bmos-brian-belski/wcm/a256e029-859d-47b0-9516-990bacfebd89/

[16] “Warren Buffett: Why stocks beat gold and bonds”, Warren Buffett, Fortune, February 9, 2012, https://fortune.com/2012/02/09/warren-buffett-why-stocks-beat-gold-and-bonds/

[17] 2018 Berkshire Hathaway Annual Chairman’s Letter, Warren Buffett, May 2019, https://www.berkshirehathaway.com/letters/2018ltr.pdf

[18] “The Pitchman”, Malcolm Gladwell, The New Yorker, October 2000, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2000/10/30/the-pitchman

[19] “The Pitchman, Ron Popeil and the Conquest of the American Kitchen”, What the Dog Saw and Other Adventures, April 2011, https://pen.org/what-the-dog-saw-and-other-adventures/

[20] “Even the loonie is rising against the U.S. dollar as the Fed faces currency threat: Don Pittis”, CBC, July 29, 2020, https://ca.yahoo.com/news/even-loonie-rising-against-u-080036465.html