Dear friends,

We hope this letter finds you well. Since our last correspondence, we have witnessed the failure of a few small U.S. banks, including Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and uncertainty lingers about the U.S. and European banking systems. Some investors are concerned that the failure of these few small, regional banks including SVB (and the distressed sale of Credit Suisse, a large European bank) may be a precursor to a crisis such as the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008-09. They also worry about the possible recessionary effects of a “credit crisis” (i.e., banks may pull back on lending contributing to a business contraction). To be sure, a crisis in banking can have broader economic implications, as we saw in the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2009. However, we note that recent events are best characterized as a crisis in confidence, and not a crisis related to the financial health or stability of U.S. banks, generally.

We don’t need to tell you, dear reader, that the current environment is one of trepidation. There is much concern about other economic issues including a potential recession, inflation, rising interest rates, etc. Take, for example, recent comments from J.P. Morgan CEO Jamie Dimon:

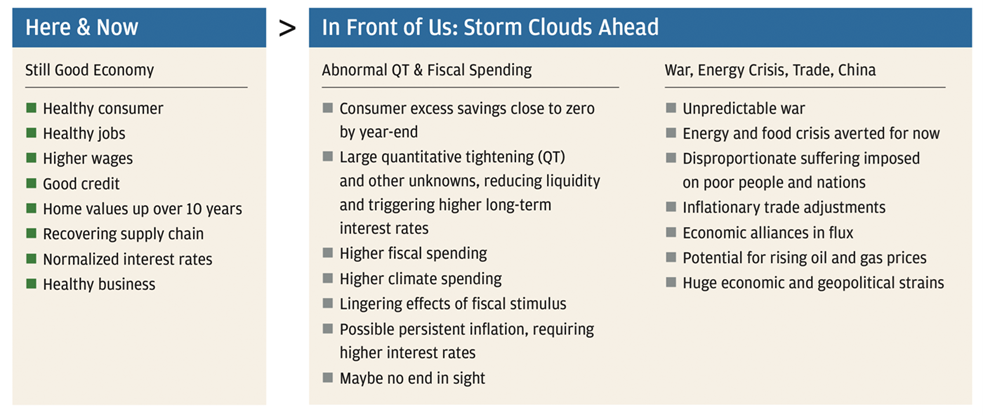

“2022 was not normal, economically speaking, and, in fact, 2022 witnessed several dramatic events — the Ukraine war began; inflation hit a 40-year high of 9%; the federal funds rate experienced one of its most rapid increases, up 425 basis points, albeit from a low level; stock markets were down 20%; unemployment fell to a 50-year low at 3.5%; and the U.S. economy was bolstered by frequent fiscal stimulus and by high and rising government debt while supply chain issues eased. In addition, work from home began to raise commercial real estate challenges and, finally, long- and short-term interest rates presented a sharply inverted yield curve, which is “eight for eight” in terms of predicting a recession. But surprisingly, the global economy marched ahead…. While the current crisis has exposed some weaknesses in the system, it should not be considered, as I pointed out, anything like what we experienced in 2008. Nonetheless, we do have other unique and complicated issues in front of us, which are outlined in the chart below[1]”:

We acknowledge these “unique and complicated issues”, but we point out that these expectations are, to some extent, baked into markets (i.e., these worries are widespread and represent conventional thought). As billionaire investor Stan Druckenmiller likes to say: the obvious is obviously wrong. “Druck” is a second level thinker who discounts the informational value of conventional thought. We don’t know if a recession will occur, but we don’t spend much time thinking about it for the following additional reasons:

- Bob Farrell trading rule #9: The late Bob Farrell was a 50-year veteran of Wall Street. Although his focus was “technical analysis” (studying charts), he was also a keen observer of investor psychology. Rule #9 says: When all the experts and forecasts agree – something else is going to happen. True, this insight is empirical / anecdotal but nevertheless, chock full’ o wisdom in our experience;

- The track record of prediction about markets, economies, and “macro” or geopolitical event is not good. This information has little-to-no value for the purpose of making investment decisions and it may very well shake you out of your stocks, a detriment to long-term returns. Economies are profoundly complex. We have humility about our, or anyone’s, ability to forecast such things; and

- Markets and the economy are not always in sync. Markets are forward looking, and recessions are only identified in the midst or perhaps the tail end of a downturn. Sometimes the market front runs the economy and sometimes it lags. Perhaps inflation will abate and / or central banks will pause or cease hiking interest rates – a positive for stocks. No one knows.

The GFC is fresh in the minds of many investors, as is the European debt crisis of 2009-2011 – both painful episodes for stock market investors. However, there are some important distinctions to be made. First, the GFC was precipitated by U.S. banks holdings in arcane securities made up of sub-prime residential mortgages during the tail end of a bubble in U.S. real estate. The busting of the real estate bubble in 2006 put to rest the then widespread belief that home values would only go up. Howard Marks has it right – he advises that “Seven terms that investors should purge from their vocabularies: “never,” “always,” “forever,” “can’t,” “won’t,” “will,” and “has to.”

In contrast, today’s problems are centered around banks’ bond holdings (i.e., U.S. Treasuries), which have modestly declined in market value as interest rates spiked over the past 18 months. To use a simplified and hypothetical example, some banks today may have experienced a 10-15% decline in the value of their U.S. Government bond holdings (to the extent that they have any), whereas in the GFC, many large banks held tens of billions of dollars of mortgage securities that effectively became worthless. Remember the “Ninja” loans (i.e., No Income, No Job, No Assets) underlying the mortgage securities at the epicentre of the GFC? To compare these loans to U.S. Treasuries is to compare apples to pumpkins.

We also note that the issues surrounding small, U.S. regional banks such as SVB are unique. Large U.S. and Canadian banks have a different risk profile. To explain the nuances, we have prepared the following Q & A:

What happened?

The situation at SVB was unique. It was a niche bank that served a narrow group of clients – technology and venture capital companies. SVB invested a large proportion (relative to the bank’s capital) of its deposits in longer-term Government bonds, which declined in price when interest rates rose dramatically. These losses were very significant relative to the bank’s own capital. News of these losses caused their depositors to withdraw their deposits – all at the same time. A classic “run on the bank” ensued. As you will know, banks are leveraged. Generally, for every dollar of deposits they have several times that amount in loans outstanding. So, confidence is paramount.

Why is SVB different from large banks such as, say, Bank of America or Canadian chartered banks?

First, most large banks have very diversified depositors (customers). Some are individuals, some are small or large, commercial customers. Importantly, they are a very diverse group. Many of these deposits are smaller (under the limit for CDIC or FDIC insurance) and hence more “sticky” – they tend to stay put over time. SVB deposits were largely “uninsured” (i.e., amounts greater than $250,000 which is the upper limit for Federal deposit insurance). Naturally, uninsured deposits are withdrawn at the hint of trouble. Additionally, most large banks have diversified sources of revenue – from wealth management, investment banking, insurance, trust services, personal and commercial banking, etc. Simply put, large Canadian and U.S. banks have more stable funding and diversified sources of revenue.

Further, SVB invested a high proportion of its capital in longer-term fixed income securities. Many large banks do hold some longer-term bonds, but in a much smaller proportion than SVB. They did not make a large bet relative to their capital. Generally, large Canadian and U.S. banks have a lot of excess liquidity.

As well, here in Canada we have a very concentrated banking industry. The six large Chartered banks have a market share that exceeds 90%. This model differs from the U.S. and is purposely designed to reduce the likelihood of banking crises. Question: What is worse than a fat oligopoly in banks? Answer: Having to repeatedly bail out the banking system with public funds.

Will the collapse of SVB lead to a contagion?

The primary reason for the Federal Reserve bailout of SVB depositors was to restore confidence in the banking system and prevent a ripple effect (i.e., if depositors lose faith in banks, they may rush to withdraw their money leading to a run on other banks). So far, the crisis of confidence surrounding banks has only affected the weak and the mismanaged — the vulnerable.

Are current events similar to the GFC?

The factors that led to the GFC were unique and are not present today. The cause of the GFC was related to “credit” (i.e., securities tied to mortgages that lost most of their value). There is no indication of such a credit crisis today. The collapse of SVB was not related to credit losses. Following the GFC, new rules were drafted that requires banks to hold higher levels of capital relative to loans. As well, new annual stress tests were implemented. These were moves to strengthen the banking system and avoid a recurrence of the GFC. In terms of credit, banks are generally in a strong position. Highly regarded bank analyst Mike Mayo had this to say about SVB: “[the crisis at SVB may be] an idiosyncratic situation. This is night and day versus the global financial crisis from 15 years ago. [Back then], “banks were taking excessive risks, and people thought everything was fine. Now everyone’s concerned, but underneath the surface the banks are more resilient than they’ve been in a generation.[2]”

The moves by the Federal Reserve and a consortium of large U.S. banks that shored up another smaller U.S. bank with similar exposure to longer term bonds (First Republic Bank), have so far bolstered investor confidence.

There is also a possibility that large banks may benefit from a “flight to safety”. Mayo’s theme for investing in banks is “Goliath is winning”. He recently commented that, “JPM epitomizes our theme of ‘Goliath is Winning’, which should benefit both offense (market share gains) and defense (more diversified) in these less certain times[3]”.

On April 18, Howard Marks made the following comment about SVB in a memo to investors: “My sense is that the significance of the failure of SVB (and Signature Bank) is less that it portends additional bank failures and more that it may amplify pre-existing wariness among investors and lenders, leading to further credit tightening and additional pain across a range of industries and sectors[4]”.

Events like the recent crisis in confidence surrounding banks only reinforce our long-held view that investors should not discount the possibility of “black swan”, or outlier events (i.e., low probability but high impact) in making investment decisions. If it can happen, you ought to assume that it eventually will happen. Avoiding ruin (a significant and permanent loss of capital) ought to take priority over the potential for gains. It sounds counterintuitive, but great investors like Buffett think of investing as a negative art.

It is for these reasons that, before we consider the potential upside of a potential investment, we ask ourselves what might go wrong. This attitude comes from long experience and our conviction in the simple, yet powerful investment principles espoused by the investment greats such as Warren Buffett: the power of compounding, the futility of making forecasts, the negative impact of too much intervention (i.e., tinkering; “pruning”; trading; timing), the desirability of “moats” or competitive advantage, the importance of a “margin of safety”, etc. We also take seriously our duty to not only grow, but also protect your hard-earned capital.

Thinking this way restricts your investment universe. For example, do you have a strong view about who will be the winners in the commercialization of artificial intelligence over the next five to ten years? If you think it is today’s favourites, say, Microsoft or Nvidia, you must recall that before Apple came to dominate handsets, we witnessed Nokia, Palm and Blackberry passing the torch for (chronologically) the prior 25+ years. As you know, it did not end well for these once incumbents. Picking winning stocks in a nascent industry is tough, particularly when crowd favourites sport high valuations. Nvidia is an early favourite to capitalize on semiconductors for AI applications, but it currently trades for ~ 155x trailing earnings[5]. AI has a lot of buzz, at present. Bill Gates recently authored a blog titled “The Age of AI has begun”, in which he opines that “artificial intelligence is as revolutionary as mobile phones and the Internet[6]”. To be sure, there are many exciting opportunities related to AI, but at this early stage there is a risk of buying the Betamax. In emerging technologies, the market hasn’t yet sorted out which of competing technologies is superior to others and which is preferred by consumers, but what’s more, today’s opportunity set may not include the ultimate big winner(s) – somewhere, someone could be working on the new-new thing that has the potential to leapfrog or possibly obsolete today’s market darlings.

Our strategy, generally, is to focus on companies that have demonstrable and, preferably, growing competitive advantages. We seek out what Jeff Bezos calls the “dreamy business”. In his 2014 annual letter to shareholders, Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos wrote that a dreamy business has four characteristics: “Customers love it, it can grow to very large size, it has strong returns on capital, and it’s durable in time — with the potential to endure for decades. When you find one of these [dreamy businesses], don’t just swipe right, get married”.

The trick is to hang on to the dreamy business as inevitable setbacks occur. Take it from Peter Lynch: “You can be a genius at analyzing which companies to buy, but unless you have the patience and courage to hold on to the shares, you are an odds-on favourite to become a mediocre investor”. As we’ve said in prior letters, the ability to hang on to stocks is a superpower. Patience beats brilliance.

When there are “storm clouds” on the horizon, as Jamie Dimon predicts, it can be difficult to think long term and avoid “tinkering”, or reallocating to “what is working now”. More often than not, such intervention only interrupts long-term compounding. The author Gautam Baid put it best: “compounding bestows its benefits on you only after a long time, after testing your patience and conviction to the fullest[7]”.

The upshot is that there may be a silver lining to today’s sentiments: geopolitical worries and angst about a possible recession may create opportunities to invest in “dreamy” businesses at attractive prices.

We leave the last word to Howard Marks: “When investors think things are flawless, optimism rides high and good buys can be hard to find. But when psychology swings in the direction of hopelessness, it becomes reasonable to believe that bargain hunters and providers of capital will be holding the better cards and will have opportunities for better returns. We consider the meltdown of SVB an early step in that direction[8].

Best wishes to you and your family from your APEX team: Shawn, Mike, Denise N., Lisa, Marta, Denise E., John, Will and Jeannot.

Disclaimer:

This publication is for informational purposes only and has been prepared from public sources which are meant to be reliable. None of the information in this should be construed as investment advice. Speak to your Investment Advisor to learn if this product is right for you. Apex Investment Management is a tradename of Designed Securities Ltd. DSL is regulated by the Investment Industry Regulatory Organization of Canada and a Member of the Canadian Investor Protection Fund . The views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of DSL.

[1] J.P. Morgan Annual Report 2022, Jamie Dimon’s Letter to Shareholders, Annual Report 2022 | JPMorgan Chase & Co.

[2] “Silicon Valley Bank collapses after failing to raise capital”, Allison Morrow and Matt Egan, CNN, March 10, 2023, https://www.cnn.com/2023/03/10/investing/svb-bank/index.html

[3] “‘Goliath Is Winning’ – Wells Fargo bank analyst Mike Mayo upgrades JP Morgan Chase stock”, Julian Hebron, The Basis Point, March 13, 2023, https://thebasispoint.com/goliath-is-winning-wells-fargo-bank-analyst-mike-mayo-upgrades-jp-morgan-chase-stock/

[4] “Lessons from Silicon Valley Bank”, Howard Marks, Oaktree Capital LLC, April 17, 2023, https://www.oaktreecapital.com/insights/memo/lessons-from-silicon-valley-bank

[5] CNBC, NVDA: 269.52 +0.71 (+0.26%) (cnbc.com)

[6] The Age of AI has begun. Bill Gates, March 23, 2023, The Age of AI has begun | Bill Gates (gatesnotes.com)

[7] Baid, Gautam. The Joys of Compounding (Heilbrunn Center for Graham & Dodd Investing Series) (p. 353). Columbia University Press.

[8] “Lessons from Silicon Valley Bank”, Howard Marks, Oaktree Capital LLC, April 17, 2023, https://www.oaktreecapital.com/insights/memo/lessons-from-silicon-valley-bank